Researchers at Liverpool John Moores University and Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital (LHCH) have been looking at the difference between doctors’ perceptions of heart patients’ quality of life and the patient’s own ratings.

Using ‘Patient Reported Outcome Measures’ (or PROMs for short), they discovered that patients and physicians often report the patients’ angina burden at clearly different levels.

The summary of the research below, by LHCH researcher Ian Kemp, explores how the development of user-friendly PROMs could help transform healthcare by enabling doctors to have a more comprehensive understanding of the patient and a genuine acknowledgement of their voice during consultations.

About PROM's

Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) could help transform healthcare according to Professor Nick Black (1). PROMs seek to establish patients’ views, symptoms, functional status and health related quality of life. PROMs can measure the degree to which a condition affects their day to day functioning and broad quality of life (QoL). Some doctors have adopted PROMs to enhance patient management but all too often PROMs data is used to compare outcomes achieved by different healthcare providers. Griggs et al (2) comment the potential of PROMs is a roadmap to restructure the clinical encounter by gathering information that is meaningful to the patient and prioritising clinical information and care needs. They conclude by saying if physicians embrace the opportunities that are presented by PROMs, the dual goals of value-based and patient-centred care can be achieved.

Spertus reports that even a standard and rapid physician assessment of heart failure burden / status / symptoms -, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) is seldom completed for each and every outpatient visit (3). Physicians tended to rely on their own assessment of their patient health status. In one study 2,252 men with prostate cancer and their physicians, researchers compared patient’s assessment of their QoL with their physicians’ assessment. 74.5% of patients reported fatigue but only 10% of their physicians believed that the patient experienced this symptom.

What if there was a significant difference between a physician’s assessment of key clinical outcomes and their patient’s own assessment of their quality of life? One example of this potential chasm is the effect of erectile dysfunction on quality of life following a procedure treating prostate cancer. An early treatment for suspected prostate cancer was nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NP). The NP procedure was intended to treat cancer found outside the prostate and the surgeon aims to avoid nerves that are involved in erections. A frequent need to urinate was a common side-effect of this type of intervention. Following surgery there was less urgency in urination and the cancer was removed. However, a side-effect reported in between 32% to 38% of patients was erectile dysfunction but this increased to 60% – 70% in community-based surgical series (4). Penson points out that patients may value sexual function so highly they are willing to choose a therapy that offers a shorter life-expectancy (4).

What Did I Do?

I investigated the difference of opinion between physicians and their patients in describing the patient’s angina burden. Angina is chest pain experienced on exertion. The full report was published in 2019 (5).

I used a large dataset from a randomised clinical trial called Stent or Surgery (SoS) (6). The 988 patients in the SoS trial were undergoing revascularisation of coronary arteries. These procedures are performed to ease the burden of angina by improving blood flow through the arteries supplying the heart with blood. As part of SoS, patients completed a PROM which included a short questionnaire including a question using the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) grading. This assesses the angina burden and grades it to between one to four, with four being the worst symptoms.

A zero indicates no angina. In the SoS trial patients completed the CCS at baseline (before their procedure) and again at twelve-months. Their physician also recorded a CCS grade to assess their patient’s angina burden at the same time-points. I was then able to compare pairs of CCS grades at baseline and again at twelve months

What Did I Find?

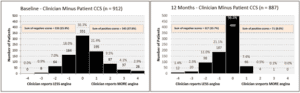

One method of reporting the differences was to subtract the patient’s CCS score from the score provided by their clinician. As each person’s score can be between zero and four, the range for the difference is between minus four and plus four. When plotting the results in a histogram (Figure 1), a plus score indicates the clinician scores higher than the patient and a minus score the reverse.

Figure 1 Baseline and 12 Months Clinician minus Patient CCS Score

What this histogram shows is that at baseline approximately a third of patients and their physicians are in agreement (a difference of zero). About a third of physicians (37.8%) score higher than patients and a quarter (25.9%) score lower. Remember, this score is prior to the patient’s procedure when angina pain had not been treated. At twelve months the position was quite different. Although more than half of patients and their physicians agreed (56.3%), just 8% of physicians scored higher than their patients, and 35.7% scored lower. Similar shape histograms were found when comparing male and female patients and by dichotomising patient age to below 65 or 65 and older.

What this shows is that there is a clear difference in the reporting of patients’ angina burden between physicians and their patients.

The findings were even more stark when I examined only those patients who were reported as angina free (a CCS score of zero) at baseline and twelve-months (Figure 2). Just one physician reported a patient to be angina free at baseline (0.1%) but at twelve-months, physicians reported 72% of patients to be angina free. By contrast, 7.7% of patients reported themselves angina free at baseline and 50.6% at twelve-months.

Figure 2 Difference and associated 95% CI for trial subjects reported as angina-free by Clinicians and Patients at baseline and at 12 Months

Why Is It Important?

PROMs are attempts to measure quality of life. This presents several problems. What exactly is ‘quality of life’? It is easy to measure procedures performed, prescriptions written or mortality rates. These measures are quantitative and can be costed, but could be said to be intermediate outputs (7). These intermediate values are not valued in their own right by patients, but on the effect on their health. The National Health Service (NHS) is not just about dealing with pathology but also in promoting health for individuals and society in general.

Spertus suggested the use of the vowels for PROMs; they need to be Actionable, Efficient, Interpretable, Obligatory and User-friendly (3). To be actionable the physician must be aware of the PROM data and be prepared to take the data into account in treatment decisions. In the example I have given in Figure 1, the angina burden reported was different between the physician and their patient. Would the treatment be different if the clinician were aware of this? If a PROM is efficient it can provide rapid and easy to understand data to the physician in a busy consultation, freeing up time. A PROM should be interpretable by a busy physician, and this presents a significant challenge. A scale of 0-100 does not carry the same clinical significance as, say, a systolic blood pressure of 210. A means of associating a PROM figure with prognostic outcome needs to be developed. Making PROMs obligatory already happens in a few instances, for example for hip and knee surgery. However, these data tend to be used at a strategic level, rather than during consultations with individual patients. If PROMs data was linked to a financial incentive that may change their use at local, patient consultation level. Making a PROM user-friendly is a further challenge. I know from my work that to convert an individual PROM into a numeric value requires several stages and will include dealing with missing values. This is best dealt with by a computer programme.

Finally, I suggest there is one significant obstacle to the day-to-day inclusion of PROMs data in clinical practice. Dealing with this obstacle could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the patient and a genuine acknowledgement of their voice. This final obstacle is changing the culture amongst clinicians and NHS managers. To what extent are physicians, surgeons, managers and other paramedics prepared to relinquish the power of having sole responsibility and accountability for patient care? This could determine the creating of a truly authentic collaboration between healthcare provider and patient. This demands a new kind of understanding of the difference between clinical outcomes and the patient’s own assessment of their QoL.

We could all do with remembering the famous quote from Dr William Osler (1849 – 1919) who said “Listen to your patient” “He’s telling you the diagnosis” (8).

If you would like to know more about the PROMs study, please contact Professor Paulo Lisboa, School of Computer Science and Mathematics: P.J.Lisboa@ljmu.ac.uk

You can find the research report findings published in International Journal of Cardiology, 293. 25 - 31 (2019): Kemp, I, Appleby, C, Lane, S, Lisboa, P and Stables, RH: A comparison of angina symptoms reported by clinicians and patients, pre and post revascularisation: Insights from the Stent or Surgery Trial.

-

Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167.

Griggs CL, Schneider JC, Kazis LE, Ryan CM. Patient-reported Outcome Measures: A Stethoscope for the Patient History. Ann Surg. 2017;265(6):1066-7.

-

Spertus J. Barriers to the use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(1):2-4.

-

Penson DF. The effect of erectile dysfunction on quality of life following treatment for localized prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2001;3(3):113-9.

-

Kemp I, Appleby C, Lane S, Lisboa P, Stables RH. A comparison of angina symptoms reported by clinicians and patients, pre and post revascularisation: Insights from the Stent or Surgery Trial. Int J Cardiol. 2019;293:25-31.

-

So SI. Coronary artery bypass surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention with stent implantation in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (the Stent or Surgery trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9338):965-70.

-

Devlin NAJ. Getting the Most Out Of PROMs. The Kings Fund; 2010. Report No.: ISBN: 978 1 85717 591 2.

-

Schwarcz J. Would Osler stand by his famous quote today? : McGill University; 2017 [Available from: https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/controversial-science-health-history-news/would-osler-stand-his-famous-quote-today.